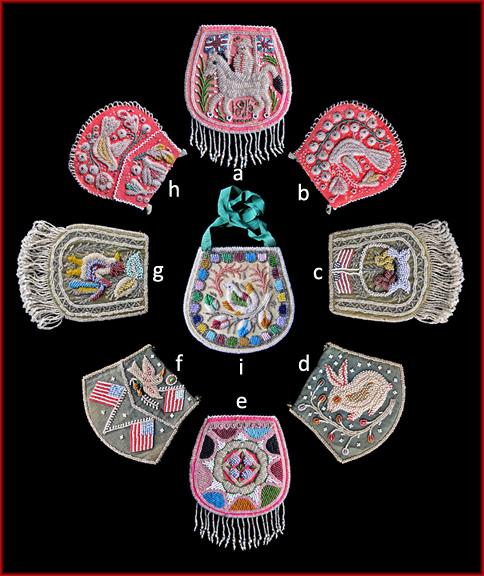

By the turn of the twentieth century, the fabric upon which the Mohawks beaded their bags and other souvenirs was characteristically a bold color. A group of exceptional bags from this period is illustrated here. The beading style in this period was often a form of raised beadwork, a type of lane stitch that had more beads for a given length of thread than normal, causing the string of beads to form an arch. The faded fabric on the bag with the rabbit (example d & f) was once a bright blue. The center bag (i) is dated by a period note with the inscription “Penny-bag, July 4th, 1914,” and it was signed “James Lone Dog.”

From about the 1890s to the outbreak of the First World War, a hot, vivid pink textile was in vogue. Other fabrics colors upon which the beads were sewn were purple, blue, brown, green, red and beige. Many of the flat bags from this period were decorated with floral and leaf patterns, but the pictographic examples were very inventive. Birds were prominent on these, but other pieces incorporated rabbits, lions, camels, cats, ducks and a host of other creatures - occasionally even human figures.

Native beadworkers were exposed to wild and fanciful animals while they travelled with the Wild West shows and circuses and this could, in part, explain their appearance in the beadwork. Books and magazines were another possible source of inspiration.

An unusual bag from this period (example c & g) has a rooster on one side and American flags with two chicks-in-a-basket on the other. Done in the raised beadwork style, it’s an exceptional example from the early 20th century. It incorporates a crystal bead spiral edging and a crystal beaded fringe. Commoditized Mohawk beadwork that incorporated US flags were no doubt made for sale in US markets, but export duties jeopardized the Kahnawakes’ livelihood so in October, 1898, 44 Kahnawake women wrote to the US Congress requesting they remove tariffs that threatened the sale of their “beadwork and Indian novelties” in US markets.

Flags appear on Iroquois beadwork from time to time. Some large pincushions had this motif as early as 1876, the time of the Centennial International Exhibition, the first official World’s Fair in the United States. In 1901, the Pan American Exposition (PAE) may have stimulated the manufacture of patriotic mementoes too, as a number of dated pieces with flags appear about this time as well. The PAE was a world’s fair type event that was held in Buffalo, New York. Some 700 Indians from 42 tribes were represented. There was a Wild West show on the grounds and the Haudenosaunee had a Six Nations exhibit, comprised chiefly of bark huts, and they were no doubt selling their crafts there too. These expositions were events that expressed or inspired love for one’s country and the Mohawks may have fashioned these pieces to appeal to the patriotic feelings of their patrons.

The bird depicted on the flap of example (f) likely represents an eagle holding an arrow in its talons. It’s interesting to note how this side of the bag delineates a predator while the other side (example d) depicts its prey. Whether or not this was intentional is unknown.

An exceptional bag from the first quarter of the twentieth century has a figure riding a horse and carrying the Union Jack (example a). Beaded on that bright, hot pink fabric that was prominent on Mohawk work during this period, it is dated 1915, in beads.

Besides selling in Montreal, the Mohawks also sold their crafts at Upper Canadian Provincial Exhibitions (UCPE). A number of Kahnawake artists entered their work in the 1858 UCPE in Toronto. Though most of the prizes were awarded to Akwesasne participants, Lewis Jackson of Kahnawake was recognized for three beaded bags and two beaded caps that he entered. Many of the contestant winners were announced in the newspapers and some of them were men, but it’s not clear if they were entering the work of female family members or their own (personal communication from Sherry Brydon).

They also had retail outlets in Quebec City. A photograph in the collection, not shown for lack of space, is a late nineteenth century albumen print, in which numerous fist purses, beaded boots and other Indian made crafts can be seen hanging in the windows of Talbot’s Indian Bazaar.

Niagara Falls was also an outlet for them. By the end of the nineteenth century, some Tuscarora beadworkers were objecting to competition from outsiders who were likely Mohawks from Caughnawaga.

Now two squaws have come to Niagara from Montreal, Quebec, says the local correspondent of the Buffalo Commercial, and have taken up a stand in the park close beside the faithful Tuscarora women. Of course the latter object, but they have so far said little. The Canadian squaws, it is said, brought five big trunks of work with them this season, and they have already announced that next year, Pan-American year, they intend to be on deck May first.

The Tuscarora squaws cannot see why the white man’s law does not protect them, as well as the products of the whites. Furthermore the Tuscaroras point out that years ago Tuscaroras were faithful to the Stars and Stripes … [a reference to their participation in the War of 1812 for the American cause]. People who learned of the situation in the park [Prospect Park] yesterday plainly stated that they thought the Montreal squaws should be asked to retire to Victoria Park… [on the Canadian side]. Public sentiment is that the Tuscarora should be undisturbed by foreign competition (Niagara Falls Gazette July 28, 1900:6).